The Marakon commentary is an extended version of the article “Food manufacturing: six steps to create value", first published in FoodManufacture.co.uk on July 31, 2015.

European Food: Backed into a Corner

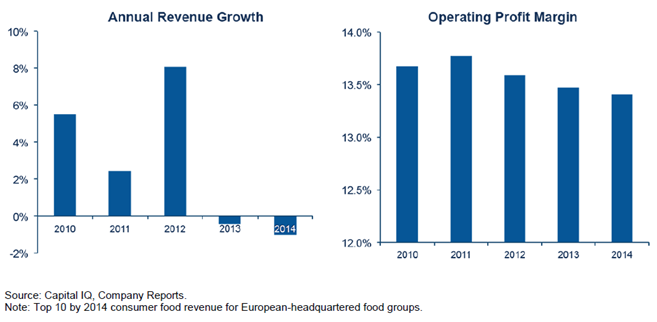

Times are tough in the European food sector. Industry overcapacity, consumer price sensitivity, the grocery price wars, and generalised retailer pressure on manufacturer economics, are all forces contributing to a material deterioration in the performance of the top 10 large and mid-cap Europe-focused food groups. This drop in performance has resulted in an evaporation of revenue growth over the last two years and a consistent deterioration in operating margin over the last three (see Figure 1).

These businesses share some common characteristics. Brand equity values are stagnant, retailer engagement and investment in the categories they participate in is at an all-time low, and, frequently, competitive activity is aggressive and price-driven. This feeds a “race to the bottom” dynamic which inevitably leads to category commoditisation and value-destruction in the value chain, with manufacturers bearing a material share of the loss.

Additionally, there are few ways out, as few trade buyers are stepping up to the plate with the confidence that they can purchase underperforming food assets and find a way back to value creation. Our corporate clients tell us that the overriding feeling is one of being “backed into a corner”.

The dynamic has, on the other hand, led to an increase in private equity-driven deal activity in this space, as corporate parents effectively put such assets on the market at very low prices. Witness for example, the acquisition of United Biscuits by Yildiz Holdings, the acquisition of the European business of Campbell Soup by CVC Capital Partners, and the acquisition of a controlling interest in Hovis by Gores Group.

Despite the extent of activity, and the attractively low asset price points (e.g., the Hovis stake cost Gore Group an astonishingly low 30 million GBP), private equity owners face a challenging task, as they are often purchasing corporate assets which are already “lean” from a cost perspective, as corporate parents have attempted to unsuccessfully save their way back to profitability before having to resort to a sale. Private equity owners are thus being asked to effectively deliver “profitable growth” and “upside” on these assets as a way to generate sufficient returns over a mid-term time frame. Our private equity clients tell us the primarily feeling is one of “discomfort".

Figure 1: Performance of the Top 10 European Food Groups

Is there a path to value creation in the structurally challenged European food sector?

Marakon believes that the answer is an uncompromising yes.

Regardless of whether the path to value creation is forged by a traditional manufacturer or a private equity group, we believe that the ingredients to success are the same.

Strategic Transformation in European Food

Our experience suggests six “must-dos” for strategic transformation in this challenged sector. We tackle and illustrate each of these in turn:

Tackle the Balance of Power Issue “Head On”, Don’t Get Trapped By It

The majority of value creation in the food sector is tied up in the “balance of power” between manufacturers and retailers. The European food retailer landscape is highly consolidated vs. the US (the top four food retailers in the UK had ~75% market share in 2013 with the equivalent in France having ~67% share, whereas the top four in the US had only ~36% share)[1]. As a result, retailers in Europe can exercise material buying and pricing power and pressure with manufacturers. By implication, in many situations the path to value creation for specific categories is mostly in the hands of retailers. If their strategic agenda is oriented around cost cutting, rationalisation, and consolidation, as it has been for the top four UK multiple supermarkets for most of the last three years, individual categories can suffer from lack of interest and investment, feeding the “race to the bottom”.

Manufacturer moves to shift the balance of power dynamic can be a good starting point for a transformation agenda. Practically, these can include moving to actively consolidate the supplier base to exercise more power and authority in retailer negotiations as the number one or two player in a given category, or moving to bypass retailers completely by adding a direct to consumer capability in the manufacturer arsenal. Dorset Cereals, for example, sells its entire range online through its own dedicated website alongside distribution through traditional retail channels.

These kinds of moves can increase market share,

redress the balance of power by opening up direct access to consumers, and put manufacturers in these categories more squarely in control of their own destiny. Effectively, our work indicates that strategic transformation is by definition much easier for the manufacturing leader or number two player from a market share perspective in a given category.

Re-Shape the Portfolio for Absolute Profit Growth

The performance of manufacturing businesses is tied up in the absolute profit growth potential of their geography, category, brand, and pack portfolio. The ideal portfolio shape therefore should be expertly optimised across the major dimensions that determine absolute profit growth: volume, pricing, cost of goods, and growth potential. Effectively this means ensuring a good balance of exposure across high volume / low cost of goods / low pricing / low growth portfolio pieces (i.e., traditional own label business) with sufficient plays in lower volume / higher cost of goods / higher pricing / higher growth portfolio pieces (i.e., traditional branded premium business).

Secondly, businesses need to make portfolio optimisation decisions holistically and not marginally, by constantly re-evaluating total portfolio shape and its expected contribution to absolute profit growth. This is important because marginal business can seem profitable when evaluated on a stand-alone basis, but will then drive complexity costs and operational inefficiencies in other parts of the system that can then impact total business operating margin (vs. gross margin per unit). This is why so many businesses in the food manufacturing space wake up to the realisation that 20% of their SKUs drive 80% of their gross profit, whereas the remaining tail contributes 20% of profit but is a significant drag on operating margin.

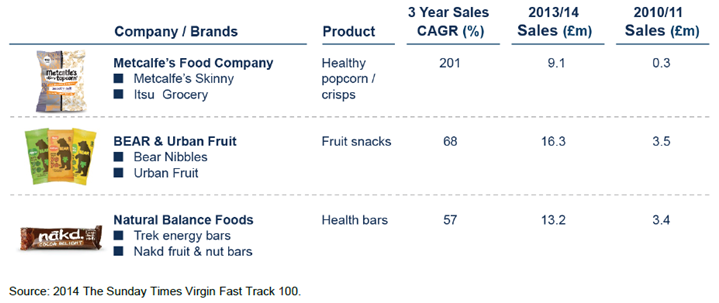

Figure 2: Market-Leading Innovative Food Companies

Find the Latent and Price-Inelastic Demand, and Be First-To-Market

Consumer tastes and preferences are changing at a dramatic pace in the food sector. The consumer health and wellness trend is here to stay, and attributes such as “high protein”, “gluten free”, “low in salt”, “organically grown” are all increasingly strong indicators of quality and consumer trust. Unfortunately, traditional food manufacturing companies are late to the game, and disruptive, scalable innovation in the food space is often driven by smaller, more nimble competitors who are able to tap into latent, price-inelastic demand. Witness, for example, the rapid growth of companies such as Metcalfe’s Food Company, BEAR & Urban Fruit, and Natural Balance Foods. See Figure 2.

Strategic transformation of underperforming food businesses must include a step-change in the ability to create value through innovation. This includes building a clear understanding of pockets of latent, price-inelastic demand, and having the ability to move quickly and at scale to secure the benefits of first mover advantage. This can include acquiring promising smaller businesses (e.g., witness SABMiller’s arguably “late to the game” recent acquisition of Meantime in beverages), or organic plays that take the company into new attractive spaces. These kinds of innovation plays have the potential of “ticking” all the absolute profit boxes – simultaneously delivering high volume, high growth, and high pricing leverage for the business in question.

Make Efficient, Targeted Use of Commercial Investment, Don’t Cut It

In businesses caught in a “race to the bottom” dynamic, the mix of commercial investment shifts from consumer-focused spend to trade spend (i.e., listing fees), as suppliers are pitted against each other by retailers, creating a contest to secure supermarket aisle space in deteriorating categories. Furthermore, as the impact of consumer-focused commercial investment is hard to quantify, above the line marketing spend tends to be one of the first items to be cut from budgets by senior executives managing businesses under severe performance pressure. Predictably, this further exacerbates the “race to the bottom” – brand equities deteriorate, categories become increasingly commoditised, and manufacturers have fewer and fewer levers in their arsenal.

Strategic transformation of underperforming food businesses must incorporate a new approach to commercial investment, on the one hand placing a larger constraint on total size of marketing budgets, while on the other hand working hard to direct marketing activity to consumers through better targeted and frequently less expensive channels.

In 2013 Cadbury used an innovative social media campaign to revive its well established Creme Egg business, which had been suffering from declining sales. It used a series of one-off posts feeding into an overall narrative on Facebook to target 16-24 year olds, who over-index on the site and are harder to reach through TV advertising. The targeted strategy was highly successful, achieving almost the same purchase intent as TV with one-third of the budget, and helping drive a 7% increase in sales[2].

Present a Wholistic, Value-Creating Mid-Term Strategy to Retail Partners

Even if traditional manufacturing businesses make a strategic choice to invest materially in direct to consumer capability, as in the case of Dorset Cereals, retailers are still going to be a critical part of the value chain that need to be engaged and brought on board to jointly drive a value creation agenda.

Despite a lot of “talk” about joint business planning in the food sector, we have observed that manufacturers still frequently fail to make clear and compelling strategic, category and commercial arguments to retail partners about how to move a category forward and create value for both parties. Retailer management is often effectively treated as an opportunity to “trade product”, the dynamic inevitably becomes adversarial despite the imperative for much closer collaboration, and retailers revert to standard behavior of trying to extract more stringent terms from manufacturers. Listing fees increase, aisle space decreases, aisle displays and merchandising standards deteriorate, and the “race to the bottom” continues.

One of our clients was the leading, primarily own label (OL), player in an increasingly commoditised food category, experiencing significant price pressure, declining volumes, and a rapidly deteriorating operating margin that was down in the low single digits. The category suffered from reductions in aisle space and a lack of in-store investment at most retailers, due to more pressing retailer priorities and a “prisoner’s dilemma” dynamic with competition regarding category investment.

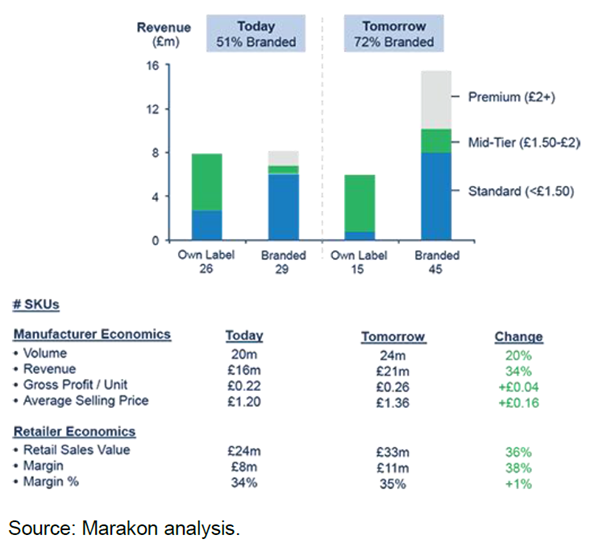

Working together, we felt that a material change in mindset and orientation was needed to change the paradigm with retailers. We therefore took the view that a new branded category leadership agenda with retailers could be the platform on which to fundamentally reverse the category dynamic.

For our manufacturing client, a shift to a higher share of branded SKUs in their portfolio would simplify the portfolio materially in terms of SKU count, improve manufacturing efficiency, lower production costs, and free up funds for additional, but targeted commercial investment in-store. The increased focus on brands would deliver a better and clearer platform for price tiering and category premiumisation when compared to own label business, while also making the manufacturer-retailer power dynamic more equitable.

Retailers also stood to materially gain from this new orientation. They were effectively invited to let our client invest in the in-store category experience on their behalf, as long as the push towards branded share of business was respected. Joint work behind the new branded portfolio led to a much improved in-store category experience and much clearer brand merchandising and pricing cues with which to engage consumers. Additionally, new innovative branded propositions would drive incremental sales by bringing much-needed new consumers into the category. Finally, retailers had a clear financial incentive to support the strategy of “rebranding” the category because our client would deliver higher margins on brands vs. own label products.

In short, the new strategy received strong buy-in and support across all the major UK supermarket multiples because it represented a strategic but grounded case for category transformation and delivered attractive economics for both parties.

Figure 3: Illustrative Economics for the Manufacturer and Retailer

Focus Primary KPIs on Growth in Absolute Profit Growth and ROIC

It is critical that the metrics used for measuring and managing performance support the strategy and encourage the right behaviours and actions across the organisation. Food manufacturers often suffer from a legacy of silo-ed functions and misaligned incentives that can make this kind of thinking difficult to implement unless very strong cross-functional ways of working are the norm. When commercial teams are incentivised with volume metrics, they can make decisions (e.g., introducing incremental new SKUs that are very small contributors to the overall picture) that, over time, can run counter to metrics important in other parts of the organisation, such as manufacturing efficiency, inventory management, and working capital optimisation.

A holistic and aligned approach to performance management is therefore required, which enables all sides of the organisation to have clearer line of sight on the two holistic metrics that ultimately matter in these businesses: absolute profit growth and return on invested capital.

Largest Barrier to Progress: Mindset and Capability

The six “must-dos” for strategic transformation in the European food sector are material and difficult, precisely because what is being described is transformative in nature.

We have laid out a set of actions that can take executives from wanting to sell an underperforming asset at almost any price to a place where they feel strong and confident about future value creation potential.

This degree of transformation would be hard to do for any business, but can be made more difficult by a legacy frame of reference and capability set that we frequently observe in food manufacturing businesses. Transformation will also require a material change in mindset and evolution in core capabilities. We highlight below some examples of the changes needed:

- Making decisions strategically, holistically, and cross-functionally, vs. tactically, marginally, and in silos

- Changing the overall leadership mindset from “managing the decline” to “creating material value upside”

- Having the organisational confidence to set the category value creation agenda vs. be a recipient of the “race to the bottom”

Thinking and behaving like a category leader vs. a supplier of low-cost product

A strategic transformation therefore is composed of seven “must-dos”, with the seventh being a material change in organisational mindset. All need to be tackled together to effect the degree of change required.

[1] Source: Kantar (12 w/e 5 January 2014), Kantar (12 w/e 29 December 2013), USDA (2013).

[2] Source: Econsultancy (14 October 2014).