In recent years the European food manufacturing sector has come under pressure from the forces of recession, rapidly changing consumer tastes, and the fragmentation of competition. Consumers have maintained the recession-provoked search for value and increased control over their health, wellness, and nutrition choices. Smaller competitors have capitalised on changes, while large, more established players have been weighed down by their legacy food portfolios. Against this backdrop, intense competition between retailers and manufacturers as well as competition across the value chain in general has depressed margins and stifled profit growth.

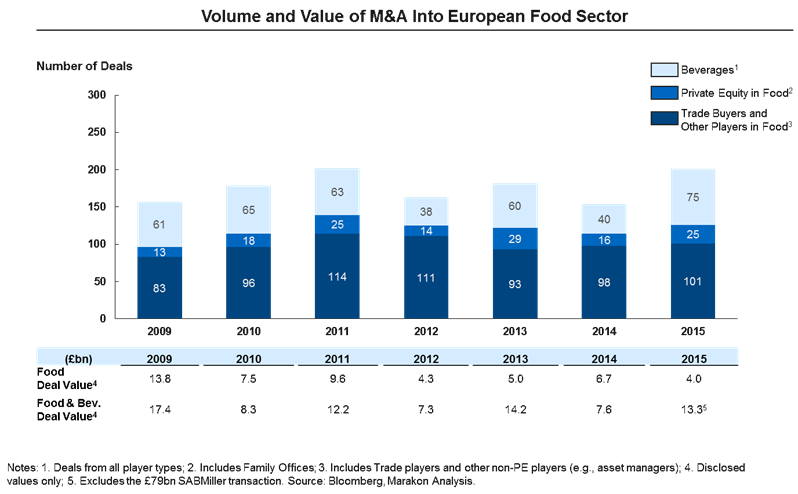

Unsurprisingly, M&A activity in the food sector has grown as players have sought to offload underperforming assets, with private equity (PE) as a material investor. The PE model tends to purchase assets at attractive prices using debt financing, add value through cost cutting and increased focus, and sell assets at higher multiples. As Figure 1 illustrates, 2015 saw the highest number of deals since 2011, with PE generally accounting for 20% of all deals.

Figure 1: Recent European Food Sector M&A Activity

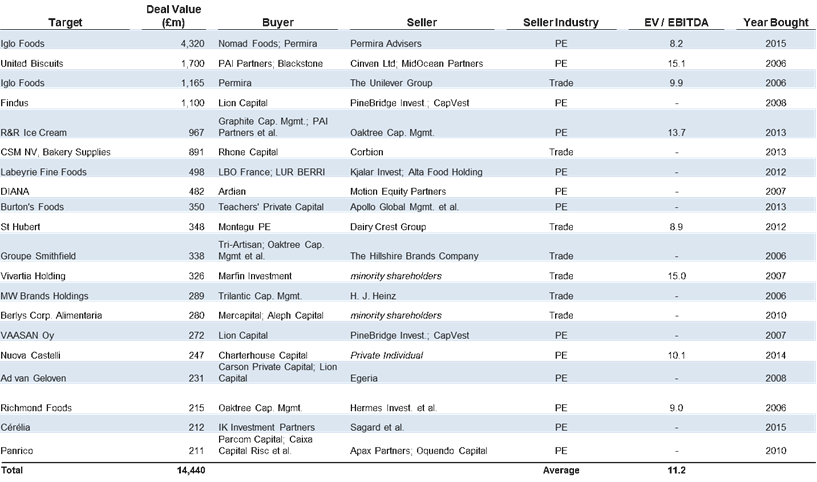

In reality however, deals have not necessarily been cheap for PE buyers. In the past 10 years, the average EV/EBITDA multiple paid for food assets by PE is similar to that paid by trade buyers (~11x and ~12x, respectively, based on data from Capital IQ). High multiples, driven primarily by intense competition for assets, including from non-European bidders keen to gain exposure to Europe (e.g., acquisition of Quorn by Monde Nissin, a Philippine conglomerate at an EBITDA multiple of ~14x), make additional value creation more challenging.

In addition, the cost-focused operational streamlining that has traditionally been employed by PE investors is constrained by the fact that previous owners have often already streamlined these businesses. Secondly, manufacturing consolidation (i.e. the combination of factories) is also hard to pull off due to a strong ”own label” dynamic in many food categories, where retailers demand dedicated production facilities.

Finally, the recent deterioration in the debt markets further puts in question the generic PE model and its applicability to the food sector. As one example of challenges in the sector, Nomad Foods, the PE-backed acquisition vehicle driving a roll-up strategy in frozen food which also happens to be the largest PE-backed transaction in the food space in the last 10 years (see Figure 2), recently announced a new round of cost-cutting as investors reportedly start to question the fundamentals of its business model. (Financial Times, February 17, 2016)

Figure 2: 20 Notable Purchases by PE Firms (Capital IQ data)

In summary, the traditional PE model (buy low, leverage, cut costs, improve focus, sell) is increasingly insufficient to deliver material value creation in this challenged sector.

The way out of this quagmire is to embark on a journey that fundamentally resets the business on a strong trajectory without compromising on near-term performance. The key ingredient is the delivery of accelerated and self-funding, profitable revenue growth. In our experience, the key elements required to do this include a mix of “no regrets” moves with calculated risks into new spaces:

- Portfolio simplification (fewer, bigger SKUs) to de-clutter the aisle, connect better with consumers, and drive COGS savings from higher manufacturing efficiency

- Portfolio enhancement (improved products, higher prices) and pricing simplification (clear tiers, more efficient promotions) for higher margins

- Material innovation vs. incremental new product development, taking brand and product inspiration from the broader wellness space

- A shift in marketing mix (digital and social) to more effectively emphasize what increasingly matters in food (provenance, quality of ingredients, recipes) vs. what matters less (brand)

- A holistic reset of economic assumptions and collaboration with retail partners. The key is unlocking collaboration that delivers profitability to both parties, while determining clear and separate roles for branded and own label businesses.

- Direct to consumer access and distribution to, at least partly, disintermediate the retailer

The reset requires businesses to work in a highly sophisticated manner integrating the best thinking from the Finance, Marketing, Sales, and Manufacturing functions, while still moving at pace.

We ask the question of whether the traditional PE model needs a re-think in the food space.

Christine Delivanis is a partner at Marakon, a boutique management consultancy, and leads the European Consumer Goods Practice. She has 17 years of experience advising executives in the consumer goods sector.

The views expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not reflect or represent the views of Charles River Associates, Marakon, or any of the organizations with which the author is affiliated.