Technology and innovation are essential components of business strategy in the oil and gas industry. Having secured access to large volumes of tantalizingly close-to-commercial hydrocarbons, most executives sign up for the technology and innovation projects that promise to finally bring in the cash. Overall technology spending has increased markedly over the last 5 years, as national oil companies ramp up their R&D spend and majors maintain theirs. Yet those same executives cite “making technology work” as one of the hardest challenges of the industry. In this article, we highlight what oil sands operators – as owners of the largest volumes of marginal barrels and growing investors in technology – are doing to increase the odds of success.

Oil from oil sands is expensive to produce. You either have to dig it out, or steam it out. Neither option sounds particularly attractive compared to flowing oil through conventional wells. And yet, oil sands are expected, and some would say required, to play an important role in meeting the world’s energy needs with production forecast to grow at a robust 7% compounded annual rate over the next two decades.

- Oil Sands Project average capex: $1 billion

- Break-even oil price for new project : $60-100/bbl

- Current oil price: $90-100/bbl

- Average annual technology spend by Oil Sands companies: > $300 million

- Rate of increase in annual technology spend in 2011-2013: 2x p.a.

However, many of the large-scale projects slated to deliver this production are looking marginal even at $100 per barrel of oil. The fear is that escalating costs and falling oil prices will push them under, and then capital and people will shift to better opportunities, such as shale oil. Operators have a window in which to improve the economics and demonstrate a sustainable business model.

For many of them, this means finding, adapting, and applying technologies and innovative practices that will substantially lower the total cost of supply for oil sands and improve their environmental impact. For some, technology investment delivers much more: a source of competitive advantage, and over time superior returns over rival operators.

Common Pitfalls

Aligning technology investments with business strategy is not new. Oil and gas operators have been working hard at this since the 1980s. But our recent work to support Alberta oil sands operators highlighted that many of the pitfalls are still common including:

- Starting with technology not strategy: developing technology priorities in a “vacuum”, resulting in technology activities out of sync with business needs

- Fragmentation: too many disparate technology efforts and insufficient coordination between business unit and corporate technology functions

- Over-commitment: defining too many technology needs as essential, making it impossible to manage all of them well

- Over-confidence: overestimating current technology strength, while underestimating resourcing needs

- Unclear focus: disparate management views regarding the optimal level and mix of technology investment, particularly on

- subsurface vs. surface

- near- vs. medium- vs. long-term

- incremental vs. step-change vs. breakthrough

-

Laissez-faire management: lack of robust decision-making criteria and processes for spending in technology research, technology development, and technology application

-

Under-deployment: struggling to deploy and exploit the (often promising) activities of academic and industrial R&D partnerships

The Performance Challenge

The spotlight is now on those oil sands producers with plans for hundreds or thousands of production wells – rather than those with open-cast mines – to demonstrate viability and innovate simultaneously. That is, they must convince stakeholders that in-situ oil sands operations are a long-term economic supply option, since most projects have yet to return their cost of capital – and at the same time, they must innovate new recovery methods to unlock lower-grade resources. Otherwise, the oil and gas industry will redirect this capital towards other hydrocarbon resources.

That means getting the production technology to work at the macro level – in a sustainable and repeatable manner. The current mainstream technology for producing oil sands through wells

is steam assisted gravity drainage (known as SAGD). Although first developed in the 1980s, SAGD has taken nearly 20 years before its full commercialization, and this has only been in a small number of locations, as it is expensive (due to the energy required) and requires a highly bespoke design for each field. The challenge for operators is to refine this technology to make it work profitably at scale on the many different fields across the vast Alberta oil sands area or to develop a better alternative.

Observed Technology Strategies

We have observed that most oil sands operators are shying away from fundamental innovation and focusing instead on the short term. The majority are pursuing either a technology ‘Follower‘ or technology ‘Adaptor’ strategy and are organized around improving near-term performance optimization rather than creating and applying longer-term technology solutions.

Figure A: Technology Strategies Employed in Oil Sands

- Follower: waits for technology and resources to be thoroughly tested and proven before applying it. In theory, avoids most of the common pitfalls but often results in slow or late deployment, and finds it harder to create competitive advantage.

- Adaptor: quickly makes incremental improvements to technologies developed by others to apply to own assets/projects. Requires high level of focus and tight alignment internally, and easy exchange of intellectual property with external suppliers.

- Innovator: develops step-change and/or breakthrough technologies. Requires a strong R&D function, good integration, and high quality technology management processes and people.

Few oil sands participants follow a ‘Innovator’ strategy, mainly due to the enormous investment required and long payback periods. Developing and piloting new extraction technologies and methods (e.g., ways to accelerate the heating of the oil, ways to carry the oil to surface) often requires more than five years just to prove the concept. A further ten years could be required to reach full commercial implementation.

The realization of a technology breakthrough in oil sands currently looks to be at least 10 years away, and so oil sands operators need to have a balance of nearer-term experimentation and optimization with a view to how to potentially own or access breakthroughs in the future.

Practices That Increase The Odds of Success

Whether the broad technology strategy is Follower, Adopter, or Innovator there is the same need for deliberate and careful management of the capital, capabilities, relationships, and people essential to delivering on the results. In our experience, we find six practices that can help companies to increase the odds of making commercial gains from technology investments, and thereby create more value from their yet-to-be produced resources:

1. Clearly define ‘business-driven’ technology needs and narrow down the commercial challenge

In order to strengthen the technology portfolio’s alignment with the needs of the business, a deep understanding is required of the challenges faced by each asset and the role technology could play to overcome these challenges. Unlike early entrants to the Alberta oil sands, most of today’s operators face challenges associated with lower quality (second and third tier) oil sands, which are either in thin beds, or much deeper, and can be highly variable and mixed with other rocks. By contrast, top-tier acreages are generally comprised of thick (e.g., 35 or more meters), wide, and clean homogenous sands with high permeability and few water, gas, and/or cap rock integrity issues.

Developing these lower quality sands poses numerous geological challenges with many requiring both operational and technical solutions. Delineating each of these challenges and identifying their magnitude and impact is critical in determining and prioritizing a technology development agenda.

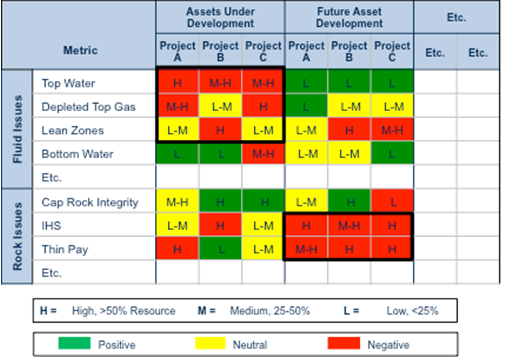

For example, the asset and project characterization illustrated in Figure B highlights the different challenges for Assets Under Development today, and for Future Asset Developments. For current projects, there are clearly water related challenges to overcome. For the future projects, there are many more rock-related challenges.

Figure B: Resource Characterization (Illustration)

Getting the commercial challenge defined early, rather than simply defining a technical problem, makes for a much more effective set of discussions and decisions on risk assessment and project selection, and risk/reward of technology in each asset and project.

2. Establish a focused set of technology ‘Grand Challenges’

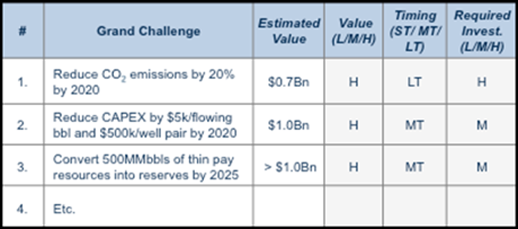

Defining ‘Grand Challenges’ is an effective way of bringing together and prioritizing the many commercial challenges. A Grand Challenge is an overarching business need that can be met by a technology breakthrough or set of technology solutions and adds material value to the company. Technology Grand Challenges are jointly defined by technology and business leaders.

Figure C below illustrates a selection of Grand Challenges typical for an oil sands operator.

Figure C: Oil Sands ‘Grand Challenges’ (Illustration)

Defining a small number (e.g., 5) of Grand Challenges has many advantages over the common practice of defining 10 to 20 technology themes:

- All staff in the company can remember five; many struggle to recall ten or more

- They engage both the technical and commercially-oriented staff, and are seen as “our challenges” rather than “someone else’s challenges”

- They specify an outcome and a timeframe in the definition; promoting alignment and checks on progress

- They provide strategic focus and help management prioritize the technology development activities and investments

In our experience, many companies baulk at defining such specific challenges for fear of failure and often end up with much looser themes, such as “Lower-Cost Wells.” This is a mistake; looser themes encourage weak discipline and lead to a lot of wasted effort on marginal activities.

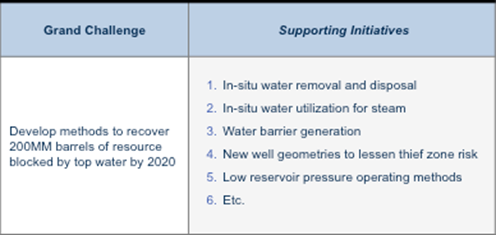

3. Deconstruct each Grand Challenge rather than simply collating technology initiatives

Companies that carefully identify a set of technology initiatives that work together are more likely to make progress than those that simply cobble many discrete initiatives together. Each initiative should be broadly defined in terms of timing, risk, funding requirements, and dependencies.

This is a natural step that follows defining each Grand Challenge but requires strong discipline to say “no” to those initiatives and ideas that are interesting but not additive to value creation. This discipline reduces the risk of fragmentation of efforts and researchers pursuing their preferred interest without any real challenge to its relevance.

The identification and high-grading of initiatives ensures that each Grand Challenge is tackled through practical concepts and specific technology projects.

Figure D: Supporting Initiatives (Illustration)

4. Regularly assess technology capabilities and competitive position

Turning a set of technology initiatives into fit-for-purpose technology portfolio requires an understanding of the competitiveness and effectiveness of the current technology activities, including where the business is advantaged and disadvantaged relative to peers.

This requires an objective and defendable assessment of the company’s technology capabilities, and also of the capabilities of suppliers, partners, and competitors. Some operators gather this through advisory boards, some through the knowledge within their own teams (particularly from those well-connected to other organizations), and some through competitor benchmarking studies.

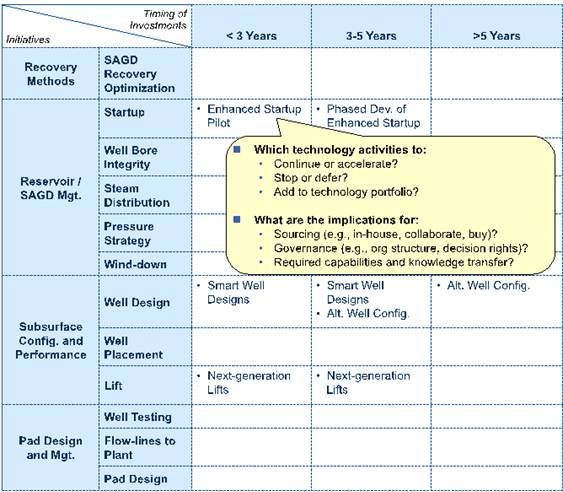

This understanding is essential to inform management decisions on:

- Adjustments to programs, including which technology projects to continue/accelerate, stop/defer, or add

- How and where to compete, including whether the business should be a Follower, Adaptor, or Innovator along core activities (e.g., well design)

- How to organize and what capabilities to have where, including governance (roles and decision rights), sourcing decisions (make, collaborate, buy), talent acquisition and development, and knowledge transfer

These decisions shape the technology portfolio and ensure it guides the business on the right near-term, medium-term, and longer-term activities.

Figure E: Technology Portfolio Ilustration

5. Plan for deployment, and then work back

Planning research and development activities is straightforward. Planning for successful and repeatable deployment is not. Although the ‘valley of death’ between the prototype and full-scale commercial deployment is well known, it is often ignored as a problem for someone else to deal with in the future. It is particularly acute in oil and gas projects because of the allocation of all the downside risk to the project or asset owner. Unlike a manufacturing company where new technology is strongly supported as an essential means to attract or retain customers, in large capital projects, it is regarded as an additional risk. This tends to lead to a very conservative take up of new technology, even if there is widespread understanding of the potential benefits.

Operators can encourage more deployment by taking on some of the risk at the companywide level through a special deployment fund, by setting technology deployment targets for asset owners, and by setting up and funding discrete technology deployment organizations to better commercialize the technology.

Companies therefore need to address the commercialization route as early as possible, even though many of their technology projects will never make it that far.

A ‘good’ technology roadmap sets out the ‘end state’ and then defines the major research, development, piloting, application, and commercialization activities over the next 5 to 10 years to achieve that end state. is developed, along with a view of the desired end-state. It is the basis for the accountabilities, milestones, resource (capital and people) requirements, partnering/collaboration plans, performance commitments, and commercialization mechanisms required to ensure a path to the successful delivery of the technology programs.

6. Treat ‘technology management’ as a core source of competitive advantage

Making technology management part of the performance culture in the same way as, say, financial management takes time. In our experience, it takes 20 years for large operators to fully integrate technology into their way of doing business such that it creates sustainable competitive advantage.

It is therefore essential to define and reinforce ‘the way we manage technology’ deliberately and systematically as a core process. This is essential in creating the culture that sees the development and deployment of technology as a lever for winning, rather than as a side activity carried out by the ‘technologists.’

As a minimum, everyone in the company should be clear on:

- What defines success, and what culture and behaviors are needed to deliver it (e.g., encouraging and rewarding calculated risk-taking, and stopping projects that aren’t working)

- Technology governance, roles, and decision rights

- Decision processes for project stage gates, pilot selection and execution, intellectual property management, JV/partnership management, and commercialization

- The organizational structure and other essential people interactions necessary to ensure the overall effectiveness of technology development and deployment

Increasingly, in-house technology innovation is at the core of what all oil and gas companies do, rather than a choice for those that are more technically inclined. As more companies take on increasingly complex projects, whether in oil sands, deep water, highly complex fields, or unconventional resources, the ability to convert marginal barrels into sustainable cash flows will define the winners.

Those companies that not only increase their R&D spending but also develop a well thought through technology portfolio and technology management model are increasing their odds of avoiding the common pitfalls, making a good return on their R&D dollars, and building sustainable competitive advantage over their rivals.